(..) Beginning with the structure of cities, if cities grew at random the problem of the creation, distribution and shifting of land values would be insoluble. A cursory glance reveals similarities among cities, and further investigation demonstrates that their structural movements, complex and apparently irregular as they are, respond to definite principles. The basis of this similarity is that the same factors create all modern cities; commerce and manufactures, with political and social forces, being everywhere operative, the chief difference in influence coming from variations in their relative power.

Cities originate at their most convenient point of contact with the outer world and grow in the lines of least resistance or greatest attraction, or their resultants. The point of contact differs according to the methods of transportation, whether by water, by turnpike or by railroad. The forces of attraction and resistance include topography, the underlying material on which city builders work; external influences, projected into the city by trade routes; internal influences derived from located utilities, and finally the reactions and readjustments due to the continual harmonizing of conflicting elements. The influence of topography, all-powerful when cities start, is constantly modified by human labor, hills being cut down, waterfronts extended, and swamps, creeks and low-lands filled in, this, however, not taking place until the new building sites are worth more than the cost of filling and cutting. The measure of resistance to the city's growth is here changed from terms of land elevation or depression, and hence income cost, to terms of investment or capital cost. The most direct results of topography come from its control of transportation, the water fronts locating exchange points for water commerce, and the water grade normally determining the location of the railroads entering the city.

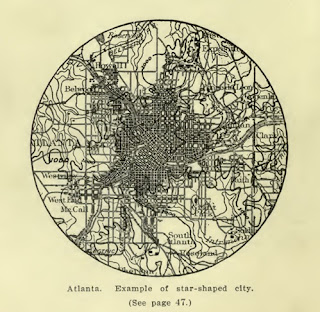

As cities grow, external influences become constantly of less relative importance, while the original simple utilities develop into a multitude of differentiated and specialized utilities, tending constantly to segregate into definite districts. Growth in cities consists of movement away from the point of origin in all directions, except as topographically hindered, this movement being due both to aggregation at the edges and pressure from the centre. Central growth takes place both from the heart of the city and from each subcentre of attraction, and axial growth pushes into the outlying territory by means of railroads, turnpikes and street railroads. All cities are built up from these two influences, which vary in quantity, intensity and quality, the resulting districts overlapping, interpenetrating, neutralizing and harmonizing as the pressure of the city's growth bring them in contact with each other.

The fact of vital interest is that, despite confusion from the intermingling of utilities, the order of dependence of each definite district on the other is always the same. Residences are early driven to the circumference, while business remains at the centre, and as residences divide into various social grades, retail shops of corresponding grades follow them, and wholesale shops in turn follow the retailers, while institutions and various mixed utilities irregularly fill in the intermediate zone, and the banking and office section remains at the main business centre. Complicating this broad outward movement of zones, axes of traffic project shops through residence areas, create business subcentres, where they intersect, and change circular cities into starshaped cities. Central growth, due to proximity, and axial growth, due to accessibility, are summed up in the static power of established sections and the dynamic power of their chief lines of intercommunication. [HURD 1903, pp. 14-16]

2020-11-12